For thousands of years mankind has sought new ways to lift heavy things.

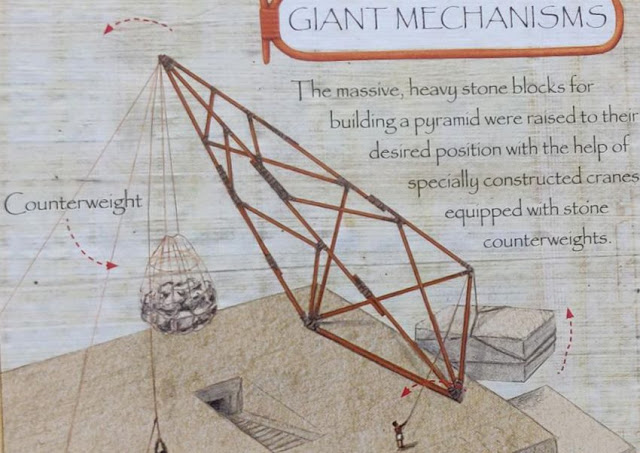

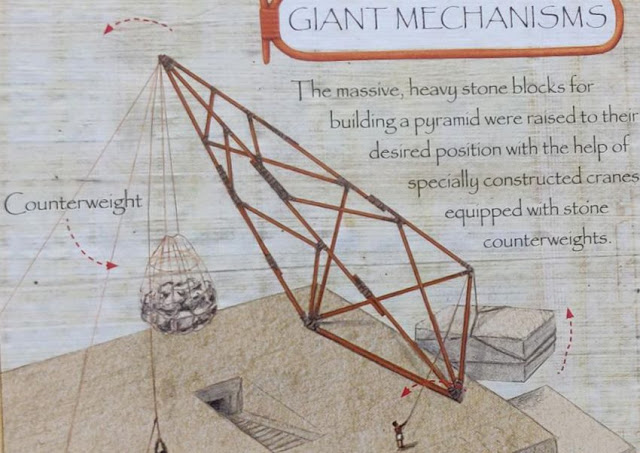

There is evidence of the world’s first ever crane-like device being used to raise building stones in Greece around 500 BC. Cranes first appeared in literature in the writings of Aristotle about 200 years later.

The Romans expanded the Greek concept of a combined pulley and jib, and continued to modify it from a 3-pulley to a multi-pulley design to lift heavier loads.

Power for these early cranes was sheer human strength. The largest early cranes, with multiple work crews and complex rope-and-pulley arrangements, were capable of lifting architectural features, like cap stones weighing over 55 tons.

As the name implies, the “treadwheel” was powered by an individual or several workers walking within a large wheel, much the way a hamster’s exercise wheel works. The treadwheel crane is mentioned in literature as early as 1225 AD, and the use of flywheels to ensure a smooth lift and eliminate “dead spots” was documented as early as 1123 AD. Most early cranes were designed primarily for vertical movement, with only limited lateral movement provided by guide ropes.

While Renaissance era cranes became more complex, requiring increased coordination and discipline among work crews, they continued to be plagued by the mechanical limitations of their predecessors: limited lateral control, uneven application of force, and extreme stresses on ropes.

Steam powered gantry cranes were used in the construction of locomotives as early as the 1870s, moving heavy boilers, fireboxes, and other components above the manufacturing floor and lowering them into place.

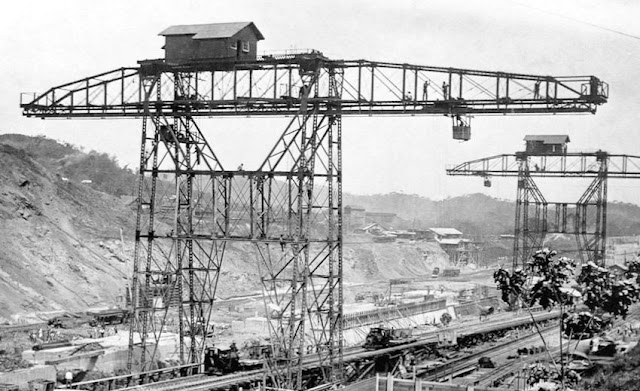

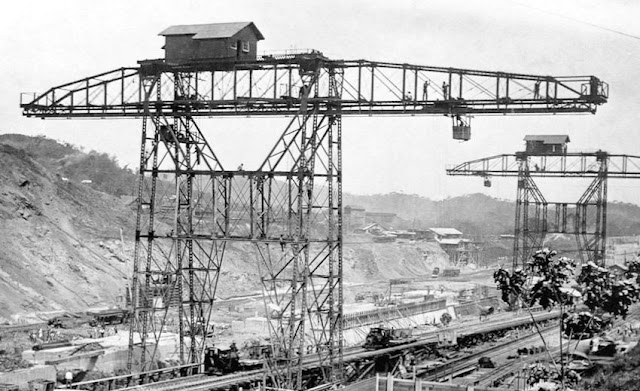

Perhaps the largest and most well known application for steam cranes was in the building of the Panama Canal in the early 1900s. Cranes of varying type, strength, and purpose were an integral part of this mammoth undertaking.

Portable and monorail cranes have allowed increased control over the lift path and have allowed crane manufacturers to work with customers in the creation of unique customized designs. Smaller work-station cranes have improved workplace safety while allowing flexibility and ease of use. The enclosed track design used by many modern industrial gantry, bridge, and monorail cranes protects components from foreign objects, rust, dirt, and ice.

The information age has also contributed to modern crane design. Control and safety systems are more advanced than ever, allowing for fluid communication between operator, supervisor, and machine.

Modern monitoring and warning systems alert operators to potential hazards. The highest-quality design and materials go into the construction of today’s cranes, enhancing their reliability, functionality and durability.

There is evidence of the world’s first ever crane-like device being used to raise building stones in Greece around 500 BC. Cranes first appeared in literature in the writings of Aristotle about 200 years later.

The Romans expanded the Greek concept of a combined pulley and jib, and continued to modify it from a 3-pulley to a multi-pulley design to lift heavier loads.

Power for these early cranes was sheer human strength. The largest early cranes, with multiple work crews and complex rope-and-pulley arrangements, were capable of lifting architectural features, like cap stones weighing over 55 tons.

The Middle Ages And Renaissance

The next great advance in crane technology came during the Middle Ages when treadwheel cranes were used to make vertical lifts in industrial settings like mines and harbors, as well as in the construction of the great cathedrals.

As the name implies, the “treadwheel” was powered by an individual or several workers walking within a large wheel, much the way a hamster’s exercise wheel works. The treadwheel crane is mentioned in literature as early as 1225 AD, and the use of flywheels to ensure a smooth lift and eliminate “dead spots” was documented as early as 1123 AD. Most early cranes were designed primarily for vertical movement, with only limited lateral movement provided by guide ropes.

While Renaissance era cranes became more complex, requiring increased coordination and discipline among work crews, they continued to be plagued by the mechanical limitations of their predecessors: limited lateral control, uneven application of force, and extreme stresses on ropes.

The Industrial Era

The introduction of iron and steel to the industrial environment did much to help bring crane technology into the modern age. Equally important was the replacement of human power, first with steam, and then later with diesel, electrical motors, and modern hydraulics. Railroads harnessed the power of steam to power cranes on “wreck trains”, used to lift derailed locomotives and rolling stock back onto the rails.

Steam powered gantry cranes were used in the construction of locomotives as early as the 1870s, moving heavy boilers, fireboxes, and other components above the manufacturing floor and lowering them into place.

Perhaps the largest and most well known application for steam cranes was in the building of the Panama Canal in the early 1900s. Cranes of varying type, strength, and purpose were an integral part of this mammoth undertaking.

The Modern Cranes

As overhead cranes have modernized, they have answered the demands for both increased strength and niche applications. Today’s cranes are more mobile and versatile. Cranes can be found on the rails, on the roads, and on towering platforms high above major cities. Harbor cranes transport tons of containers daily from ship to shore. An industrial gantry and/or bridge crane can move millions of loads within manufacturing facilities.

Portable and monorail cranes have allowed increased control over the lift path and have allowed crane manufacturers to work with customers in the creation of unique customized designs. Smaller work-station cranes have improved workplace safety while allowing flexibility and ease of use. The enclosed track design used by many modern industrial gantry, bridge, and monorail cranes protects components from foreign objects, rust, dirt, and ice.

The information age has also contributed to modern crane design. Control and safety systems are more advanced than ever, allowing for fluid communication between operator, supervisor, and machine.

Modern monitoring and warning systems alert operators to potential hazards. The highest-quality design and materials go into the construction of today’s cranes, enhancing their reliability, functionality and durability.

Comments